Normally you’d see a fancy introduction here, rife with theme

and some compelling story about the time I did something or that one thing I

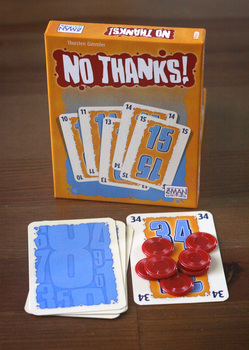

think is cool. Not today, friends. No Thanks isn’t a game about theme or

stories – it’s a game about numbers, pure and simple, and one of my favorites.

Normally you’d see a fancy introduction here, rife with theme

and some compelling story about the time I did something or that one thing I

think is cool. Not today, friends. No Thanks isn’t a game about theme or

stories – it’s a game about numbers, pure and simple, and one of my favorites.

No Thanks is always in my backpack. If I got the heads up

that I would be soon be marooned on an island, I’d make sure it was in my jacket

pocket. It’s the first game I think of when I’ve got 10 minutes to kill and a

group of gamers and non-gamers that need something easy to understand but

interesting enough to pull everyone into the “magic circle.”

You can save yourself a few minutes and just go pick this up at

your Friendly Local Game Store if you’d like, but if you want to see my strategy

guide, read on!

To start the game, the first player flips one card from the

top of the deck and sets it in the middle of the table. The player has two

choices:

1) Place a chip from his or her pile on the card and say, “No

thanks”, OR

2) Claim the card and take any chips already on it.

If the player placed a chip on the card (forever after

referred to as saying “no thanks”) then the choice moves on to the next player

in clockwise order – or anti-clockwise, if you’re feeling sporting – until the

card is eventually claimed. The player who claimed the card (and all its chips)

then flips over the next card on the deck and play begins again.

It’s important to note two things: First, that a player who

has no chips is forced to claim any card passed to him or her. Second, that the

player who claims a card also is the player who makes the

first choice on the next card. I missed this rule the first few times I played

No Thanks, and I’ve found that the game is more interesting when it’s played

correctly.

Once the last card in the deck has been claimed, players

score their cards and the player with the lowest score is the winner. Here are the

details of scoring:

1) All chips the player possesses at the end of the game are

worth -1 point each.

2) All cards are worth positive points equal to their printed

value. There is an exception:

3) If a player has cards of consecutive values in a sequence of

any length, only the lowest-value card in the sequence is scored.

For

example, if a player ended the game with the 13, 14, 15 and 18 claimed, and no

chips, the player’s total score at the end of the round would be 31 points (13 +

18 = 31). The 13-14-15 chain is scored only as 13 points, the lowest value in

the sequence, and the 18 is scored as well.

And here we find the first bit of interesting strategy in

the game – building chains of consecutive numbers allows players to take cards,

and the chips on them, without being penalized with additional points. This

means that as the game progresses, some cards are very bad for most of the

players, but good for others.

For example, if a player has already claimed the 33, and the

32 is revealed from the deck, the card is actually worth -1 point to the player

(as the 32-33 chain would score only 32 points, as opposed to the 33 points for

the single 33 card). For every other player at the table, though, the 32 is

still worth 32 positive points, which is a total that simply must be passed if

possible.

If the player who already has the 33 is smart, she’ll say “No

thanks” to the 32 once or twice and force the rest of the table to put a few

chips on the card before claiming it. This is one of the “emergent” strategies

in the game, and something I often find I have to explain to new players. I’ve

seen many players need a few rounds before figuring out how best to “bully”

people into giving up their chips. It’s an interesting dynamic that I

thoroughly enjoy.

If the player who already has the 33 is smart, she’ll say “No

thanks” to the 32 once or twice and force the rest of the table to put a few

chips on the card before claiming it. This is one of the “emergent” strategies

in the game, and something I often find I have to explain to new players. I’ve

seen many players need a few rounds before figuring out how best to “bully”

people into giving up their chips. It’s an interesting dynamic that I

thoroughly enjoy.

Though it’s easy to see that chips are good and cards are

bad, it typically takes a few rounds to figure out the “best” time to take a

card, as opposed to saying “No thanks” and giving up valuable chips. Often, players

simply run out of chips and are forced to take the card passed to them, which

can get ugly in a hurry if the rest of the table is aware of the player’s

poverty.

For a game that plays quickly and involves a small number of

moving parts, No Thanks provides a bunch of interesting choices. It’s not

uncommon for our table to offer friendly, “unbiased” advice as to which cards

should be passed or taken. This dynamic is another thing I love about the game,

as it brings out the rogue in me and my friends, and turns us into shifty-eyed,

persuasive ne’er-do-wells the instant the chips hit the table. There’s also

something viscerally pleasing about pushing around chips and cards while your

friends openly (and rudely, if they’re doing it correctly) question your

decisions.

I recently wrote a review of Splendor, in which I claimed

that the game felt like a mechanic that was waiting to have a great game built

around it. No Thanks feels exactly the opposite – like a game that takes a single

mechanic and boils it down to its essence. I love “simple” games that take one

or two interesting choices or interactions and parse away everything else.

Coloretto is a great example of a game that does this well, as are Hanabi,

Revolution, and Medici.

A game doesn’t have to be simple to use mechanics in

interesting ways, but it often feels like the simple games that focus correctly

are the ones that stand the test of time. No Thanks is absolutely one of these

games – I’ll keep a copy of it in my library for as long as I can count to 35. I’ve

talked before about what it means to be an “elegant” game, and it really boils

down to providing meaningful, interesting choices inside a simple set of rules

and interactions. Many bidding games fit the bill because of the nature of

interactivity among players during auctioning, but not all games capture the feel of bidding and pressing your luck

without junking up the board with components and layered rules. No Thanks keeps

it simple, and as a result presents an elegant experience that’s as accessible

as it is entertaining.

Strategy Guide

There is, ultimately, one choice to make in No Thanks, and

players make it over and over again. On a given turn, presented with a card

with some number of chips on it, the active player has to decide if that card

is worth claiming or not. It’s easy to get caught up in making decisions like

this is a two-player game, as though taking a card to screw somebody else is a

positive action. In almost every conceivable situation (except if you guarantee

a win by doing so) it’s a bad play to take points just to hurt somebody else. Put simply, if there are five players and you hurt one of

them, you’re just making the game easier for the other three, and that’s a bad

play.

That said, there are reasons why you would pass cards, and

reasons why you would claim them. I’ll do my

best to explain them as I’ve

thought about them, and I encourage your thoughts in the comments.

The card has a number

printed on it and you have chips.

I know it sounds pedantic, but you can be competitive in a lot of games of

No Thanks by just not taking cards. Cool, right? And yet, I see players

randomly claim cards to “mess with people” or “liven up the game”, which just

keeps my score low and makes things much easier on the sane players at the

table.

Seriously, if you can’t think of a good reason to take the

card in front of you and you have the ability to pass it, then just pass it.

You won’t regret it.

The card extends one

of your sequences, but not anybody else’s.

This is the “tricky” part of No Thanks that most players

miss their first couple games. Say you’ve just claimed a 31 and the 30 is

revealed. It’s your play, there are no chips on the card, and taking it

effectively reduces your score by 1 point, since your sequence now starts at 30

instead of 31. It’s tempting to snap up the card and flip the next one, but

before you do, take a look around the table.

Has the 29 been claimed? If it has, then another player has an

incentive to take the card also, and they’ll get all those sweet chips when

they do. But if not, then you’ve got a golden opportunity to force the other

players to lower your score. First, make sure that everyone at the table has a

chip left. If you’ve been paying attention you should have some inkling as to

which players are out, if any. If nobody is out of chips, pass the 30, and

watch the other players grudgingly say “No Thanks” as they realize that taking

20-something points isn’t worth preventing you from lowering your sequence and

gaining their chips.

When the card comes back to you, take another look at the table. Can you send it around again? Will

players give you even more of their precious chips to avoid having to take

points? It gets a bit risky as you’re never entirely sure of how many chips

each player has (unless you’re constantly counting, which isn’t out of the

question) but it will likely pay off, as you extend your sequence and gain a handful of chips. Added

bonus: your friends will curse you, but secretly respect your audacity and

penchant for making wise choices.

Another player is out

of chips

If you’re tempted to take a card but you know another player

is out of chips, you can pass the card around and force them to take it.

When you’d claim a card and why:

You have no chips

left.

This one’s easy, you don’t get a choice. Take that card!

You're almost out of chips, and the card has a bunch

of chips on it.

If you’re close to running out of chips, and the card’s

printed value is significantly offset by the number of the chips, then you’ve

got a tough decision to make. Early in the game it’s difficult to justify

taking any cards, unless they’re low-value and

get you some chips. If you’re able to survive the first few times around the

table without getting stuck with a high card – this should be easy to do if you

just don’t take a high card – then you’ll start to run out of chips.

|

| Probably OK to take, if you have to. |

When this happens, it’s important to critically evaluate the

card you choose to take. The average value of a card in No Thanks is 19 ((3 +

35)/2). That means that if the deck of 27 cards were randomly distributed to

all players, each player would have an average of 19 points per card.

That’s

important when you’re thinking about taking your first card. If the card minus

chips has a value of greater than 19, pass it (remember that we’re talking

about the first card you take). If

the card has a value equal to or less than 19, and it’s got enough chips to protect you for the rest of the game,

then take the card.

One caveat to this is that you don’t want to take a card

that you can’t make a sequence out of. If you were passed, say, the 21 with a

few chips on it, but the 20 and 22 were already claimed by other players, you

absolutely don’t take the card. When you’re forced to take a card you want to

leave as many chances as possible to build a sequence from that card to lower

your score during the game.

The card creates or

extends one of your sequences, and extends another player’s sequence.

Easy peasy, right? You’ve got the 21 claimed and the 22

comes by with a couple chips on it. Most of the time you’re going to snap this

up, slap a chip on the next card, and silently count your opponents points

until you have to make another decision. Just like in the above example, take a

look at the other player’s cards. If somebody else can benefit from taking the

card, then you’d best claim it first. If not, then think about passing it around

the table.

A quick note about probabilities

It’s easy to forget that there are nine random cards missing

from the deck. This means that you’re not guaranteed to see the cards that

extend your sequence, or more importantly, connect two cards you’ve already

taken. Too many times players justify taking a card because they hope they’ll

see the connecting card, but this is often the wrong choice.

If it’s early in the game, this can be an acceptable risk.

If there are 18 cards left in the deck, there’s a 67% (18/27) chance that the

card you need is going to show up during the game. (Remember that there are 9 cards randomly removed!) If there are 3 cards left in

the deck, then there’s a 25% (3/12) chance that the card you need to connect

your sequence will be in the game. It’s important to think about these odds when

you’re deciding if you want to take that risk. When it works it can win you the

game, but when it doesn’t work, you’re almost guaranteed to be out of contention.

Variants

There are a few variants I’m aware of that seem particularly

interesting. The first is to keep score over a number of rounds. Once one player's score exceeds the maximum (say, 500 points), the game immediately ends and the player with the lowest score is the winner. It’s a lot like

playing Hearts, and helps to keep players honest when they’re out of contention

in a single round. It also means that decisions are a little more involved, as it may

be advantageous to hurt a player who’s far ahead in the total score but not in the particular round.

The second variant is to remove specific cards before the

game starts, so that players know exactly which cards are in the deck. This

seems a little less interesting than removing the cards randomly, but does

allow players more information with which to make decisions.

Personally, I enjoy the random element of not knowing which

cards have been removed. I think the element of surprise is one of them most

pleasing parts about games in general, particularly when surprises aren’t

entirely deterministic in the outcome of the game. Players should be rewarded

for making smart decisions, but it never hurts to have a little variance spice

up a game.

If you’re into easy games that involve interesting

decisions, a little math, and fun banter, then go pick up No Thanks. It’s

probably the easiest game to teach in my library, and yet I find myself playing

it at every convention I attend and half the game nights I host. It’s the

quintessential “filler” game, and deserves a spot in your library.

Note: Although the game says 3-5 on the box, you can play 6

players if you give each player 9 chips to start. It works!

--

JR Honeycutt is a full-time husband and game-player, and co-host of The Nerd Nighters. You can find him on Twitter at @JayAhre or at a Friendly Local Game Store in Dallas/Fort Worth, Texas.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Keep it classy, nerds!